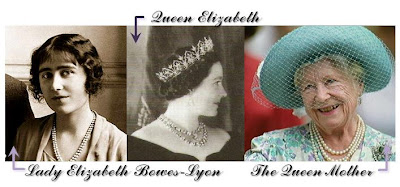

We're talking about commoner-to-princess transformations, and this is one of the originals. Lady Elizabeth Bowes-Lyon was at the head of a whole new wave of commoner marriages across the royal world. (By the way, I've added links to all the transformations we've discussed to date to the Royal Wedding Headquarters page for easy reference. Also by the way, "commoner" is defined as "not born with an HRH/HSH/etc." for our purposes.)

This case is especially fascinating when you consider the vast difference between what Elizabeth was signing up for when she married into the royal family, and what she actually got.

- What she expected: a quiet life as a second string royal. She married the second son of the King, not the heir. She should have spent the rest of her days as Duchess of York beside her husband and their children.

- What actually happened: abdication. Life as a war-time Queen consort for a nation that needed comfort and encouragement, during a time when monarchies weren't faring so well. And then a half century of widowhood, left to redefine the role of Dowager Queen on her own.

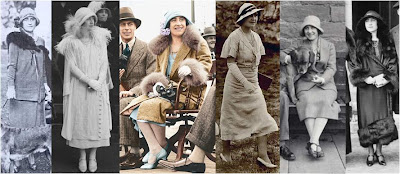

She wore a lot of Madame Handley Seymour (same designer that handled her wedding gown, and would handle her coronation gown) and even some Lanvin. The styles of the day weren't particularly flattering for her, but it didn't really matter. She was not a figurehead, and those weren't the media-centric times we live in now.

The problems came with George VI's ascension. The abdication of Edward VIII placed the monarchy in an unstable position during an unstable time. Elizabeth and her husband now needed to become those figureheads they'd never intended to be. The sartorial question at hand: how do you create a style for a new Queen when the new Queen isn't exactly the whip-thin model required to best show off the fashions of the day? (Unlike Princess Marina, with whom she couldn't compete in the chic stakes, or the Duchess of Windsor, with whom she wouldn't have deigned to compete.)

Enter: Norman Hartnell, court couturier to the aristocratic and well-off. So the story goes that George VI himself showed Hartnell the romantic Winterhalter paintings of the past and proposed he create something of the kind for Queen Elizabeth.

The look Hartnell settled on was one straight out of a fairy tale: there were day suits but there were also copious amounts of lace and tulle. And he hit the iconic button right away by creating the famed White Wardrobe for Queen Elizabeth's trip to Paris (a topic which we must revisit in depth later on). These looks date from the same time as Wallis Simpson's chic and slender bridal dress, which really emphasizes how unique the Queen's new look was.

And then the war hit. Tulle in the day gave way to smart suits better suited for climbing through bombing rubble. Hartnell dressed her in soft colors but not mourning black, to convey hope.

The Queen was on the receiving end of some open hostility for continuing to wear her jewelry (pearls and a brooch, always), high heels, and custom-made clothes while visiting victims of the Nazi bombing. Her response? She explained that people that came to see her dressed their best, and she wanted to do the same for them.

In 1952, at only 51 years old, her husband died. The role of royal widow was one that needed some padding out. She styled herself as Queen Mother, and set herself into a fashion trend of softly draped dresses and coats in pastel colors. And always, always, topped off with a hat: upturned brim with netting. In the evening, she stuck with her frilly gowns in sugary colors and narrowed her tiara selection down to just her favorites.

This is called having a lifetime pass in the style department. After abdication, a war, and early widowhood, the Queen Mother wore whatever she liked. And did whatever she liked, too: she wore a hat to Edward and Sophie's wedding even though the invitation specifically requested that no hats be worn. Not even the Queen took that kind of liberty; she wore a fascinator-headdress sort of thing. The Queen Mother lived out the rest of her pastel days in splendor, passing away at the age of 101.

A lot of the transformations we've encounter thus far have been primarily sartorial. This one is more; this is the building of an icon that an entire country rallied around. One can't help but wonder if the rest of our transformations will continue in such a vein.

No comments:

Post a Comment